A series of lectures by James Trapp, a distinguished British sinologist, Chinese literature translator, and visiting professor of Xi’an Fanyi University are hosted to advance professional expertise of our teachers and students in Chinese cultural translation and promote international academic exchanges. On May 22, Professor Trapp shared his experience in translating Laozi’s Tao Te Ching with teachers and students from three parts--textual evolution, philosophical interpretations, and cross-cultural communication in a globalized world.

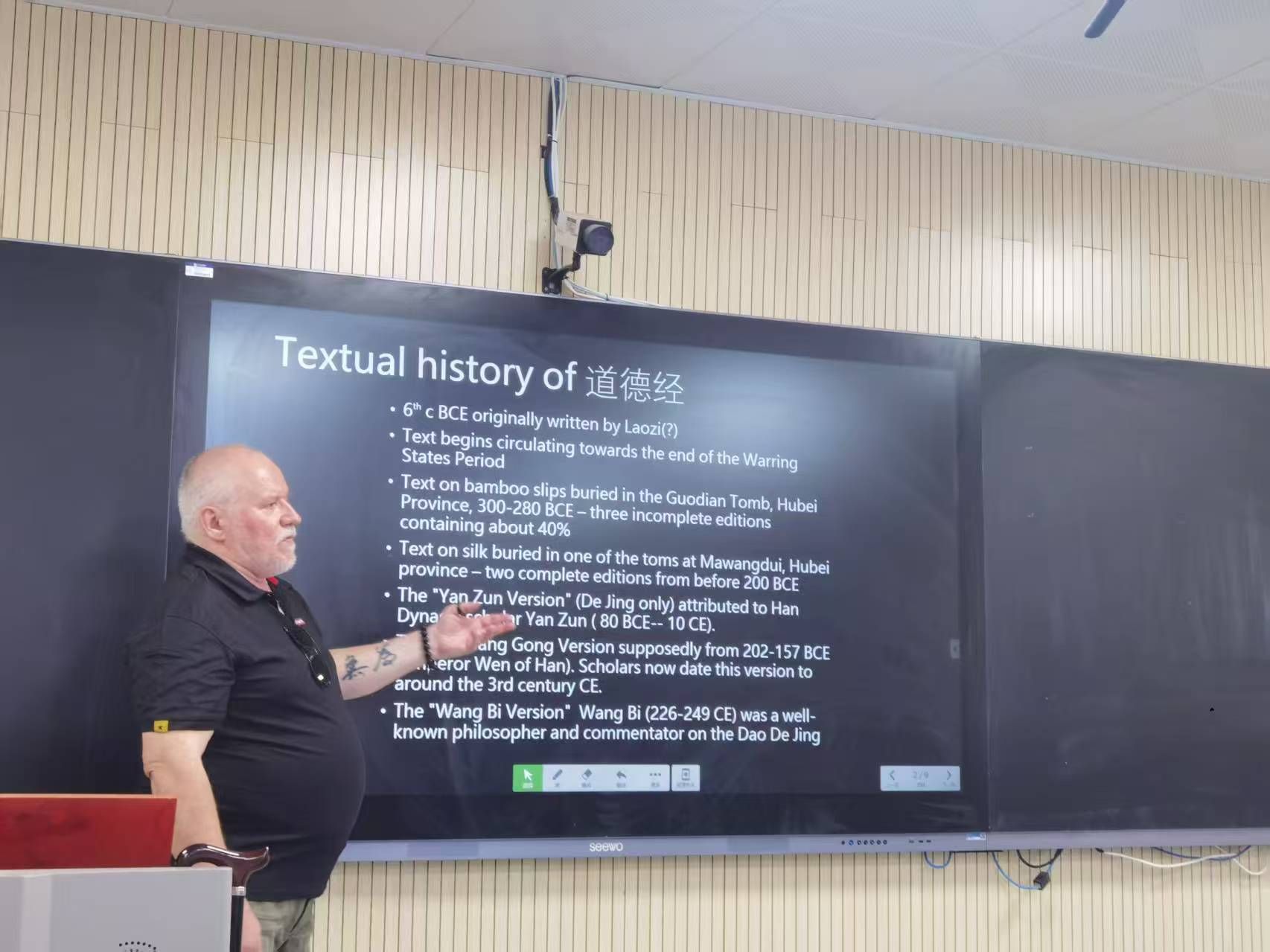

Decoding the Mysteries of Its Origin

Trapp opened by demystifying the origins of the Tao Te Ching which has been widely believed to be a compilation of philosophical fragments from around 300 BC rather than a single-authored work. Archaeological discoveries, such as the bamboo slips unearthed from the Guodian Chu Tombs (containing 40% of the modern text) and the complete silk manuscript from the Han Dynasty Mawangdui site, have reshaped scholarly understanding of its textual fluidity. He reminded translators of its potential later interpolations, emphasizing how version disparities impact translation fidelity.

Translation as Cultural Negotiation

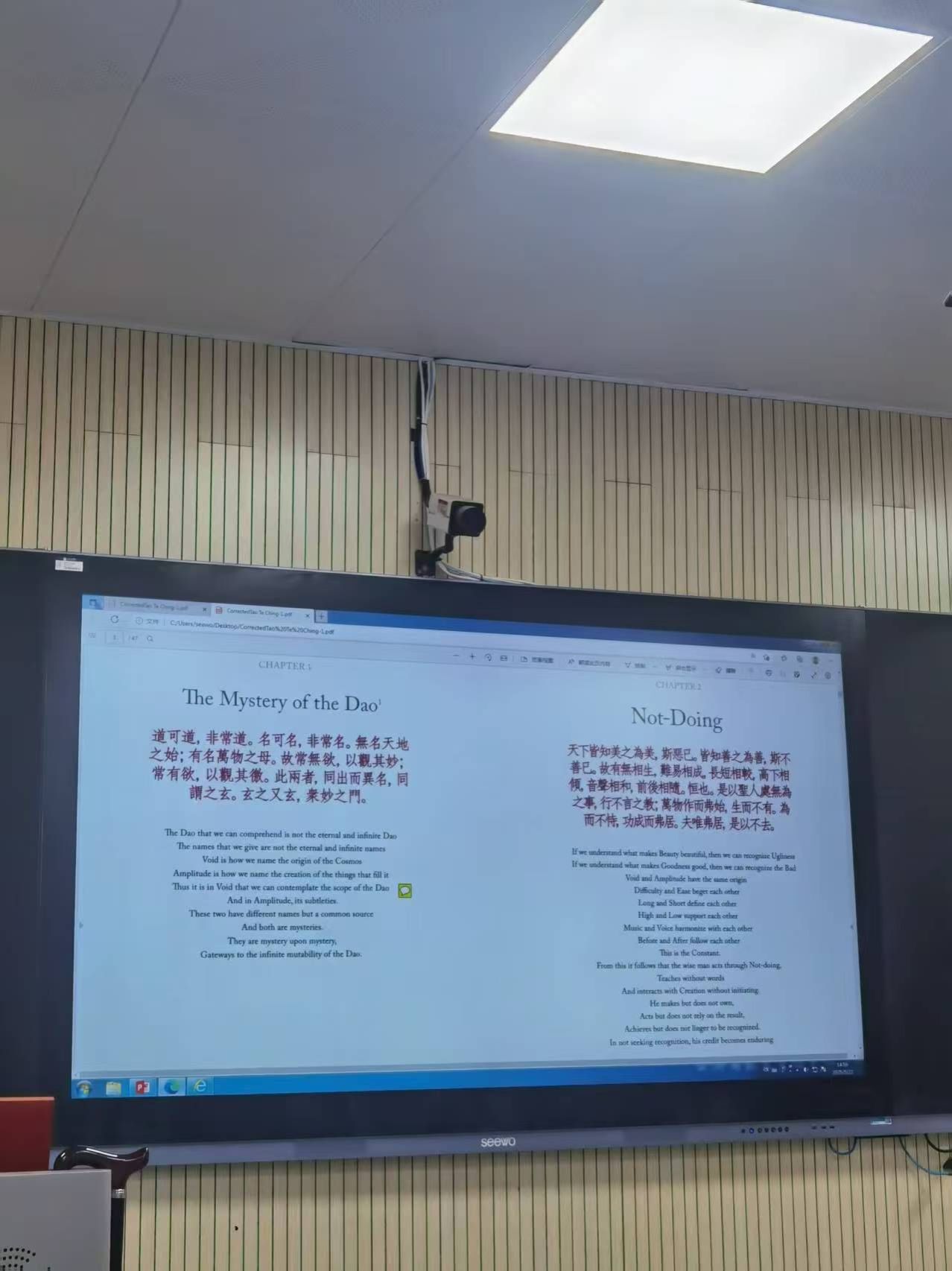

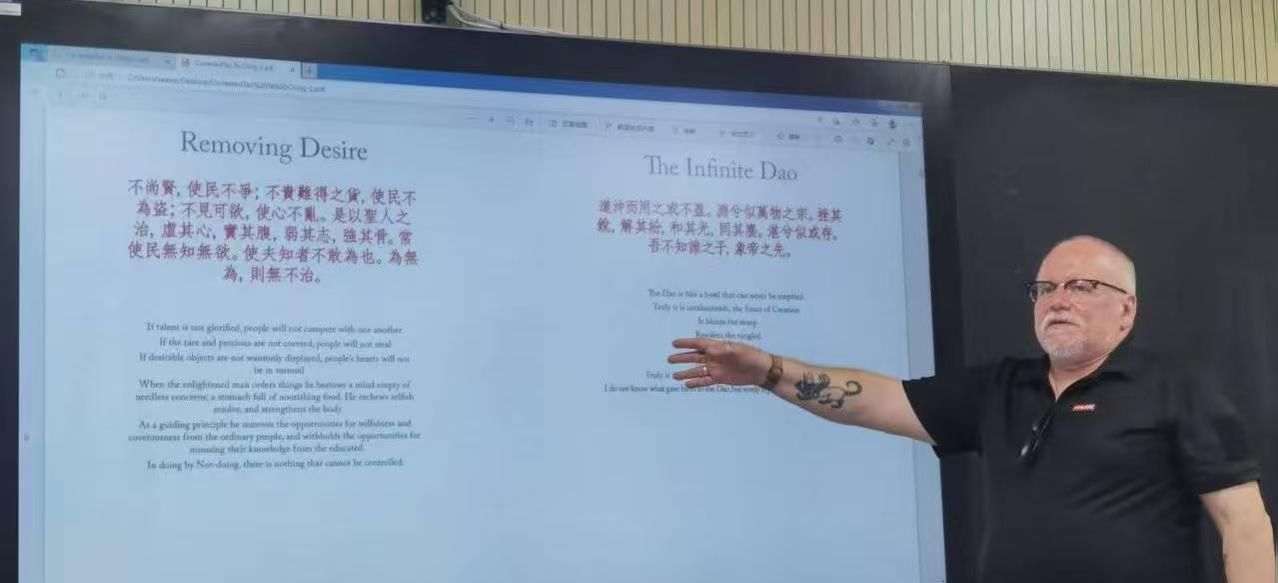

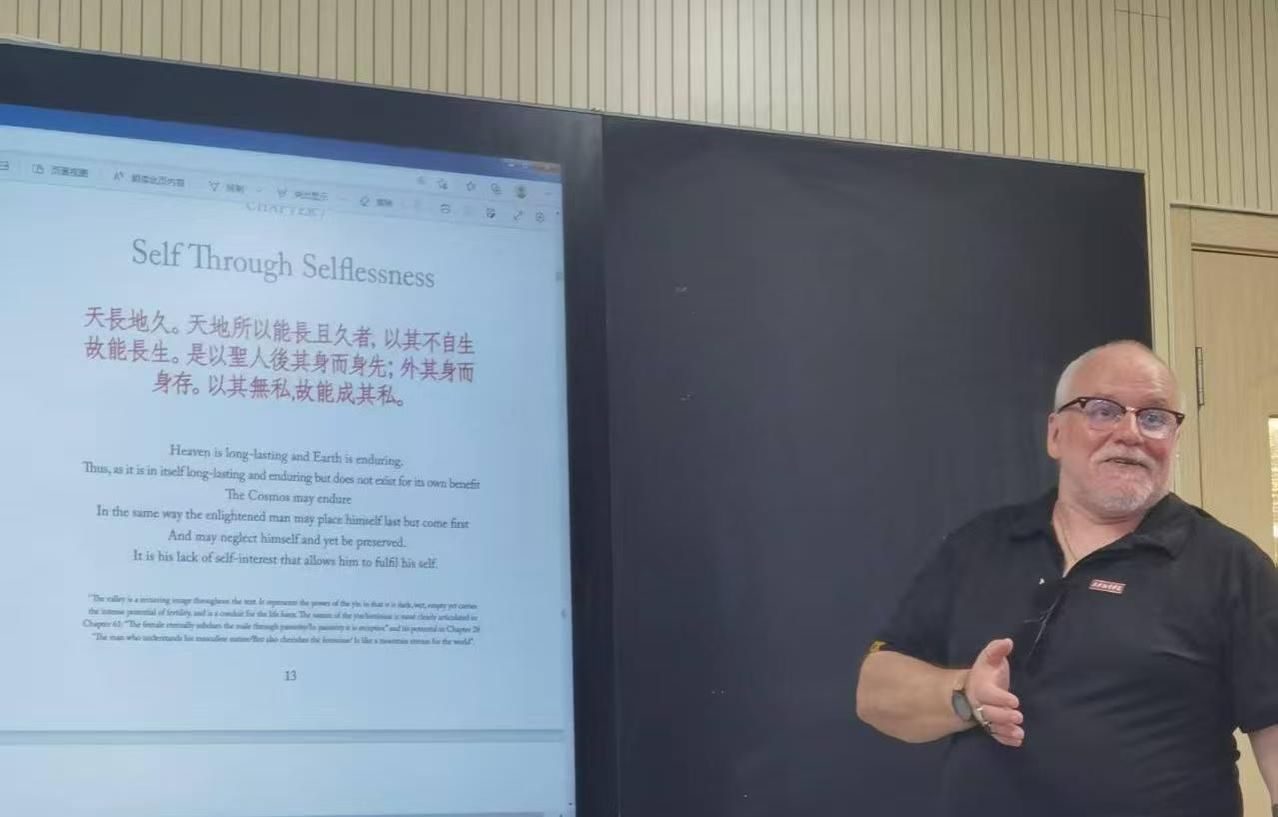

As the world’s second-most-translated book, the Tao Te Ching serves as a litmus test for cross-cultural mediation. Professor Trapp highlighted the challenges posed by classical Chinese’s semantic ambiguity, exemplified by the iconic opening line: “The Dao that can be spoken is not the eternal Dao.” He suggested that translators should be flexible in translation. For example, when rendering classical Chinese philosophical terms like wuwei (无为) into English, translators must employ creative transcreation to bridge the conceptual gap between Taoist epistemology and Western metaphysics. Trapp also addressed persistent cross-cultural misunderstandings, such as superficial comparisons between Taoist “compassion” and Christian “love thy neighbor.” He advocated for immersive cultural engagement—like guiding foreign visitors into the life of locals—to dismantle stereotypes, and for balancing cultural commonality with respect for distinctiveness.

Letting the Text Speak

With his practical advices, Trapp urged translators to prioritize original commentaries over secondary interpretations, enabling the text to “speak for itself.” This approach, he argued, is a better way to offer readers a more faithful rendering of the source text.

The Tao Te Ching’s 2,500-year journey—from bamboo slips to digital editions—epitomizes the enduring dance between linguistic barriers and intercultural dialogue. As Trapp remarked, “Translation is not replication, but a catalyst for civilizations to co-create new possibilities.” In an age of globalization, this ancient text continues to reinvent itself, proving that the Dao indeed “flows ceaselessly.”

By Zhang Jie , Reviewed by Cheng Xinyi